For Children and Ensembles

All games and exercises require directed attention; that is they cannot be successfully engaged with distracted attention. The ones described on this website are intended not only to develop your musicianship, spontaneity and creativity, but to help you develop a stronger capacity for attention.

You are welcome to make use of these exercises for yourself or your students, and you are encouraged to alter them as needed. You may notice that I try to credit others where an idea has occasionally been taken from another source. I feel that doing so provides links to additional material and it can enhance confidence in the credibility of the material. In fact, I would say that there are rather few truly original ideas anywhere in practice or print. We have all stood on each other’s shoulders, and it’s good for your students to be aware of that, since they will be standing on yours.

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS FILE:

*Introductory note to teachers interested in using this material

Playing for ‘The One’ - letting someone know that their movement is being supported

Exercise: Morphing and passing -

Circle Clap ~ (Locating yourself)

Circle Clap ~ a Developing Peripheral Vision

Circle Clap ~ b (no visual cues)

Circle Clap ~ c (with acceleration)

Finding My Space - a (Musical Rests)

Finding My Space - b (Finding a Point of Emptiness)

The Clapping Game (Looking for Nothing)

Circle Clap Left-Right - moving a sound around a circle

Pace and Stride - working with two values that are easily conflated

Friends and Enemies - staying close to ‘friends’ and distant from ‘enemies’

Body Percussion: ‘Orchestrating’ a rhythm with the body

Three Dalcroze Eurhythmics Exercises (“Quick Reaction,” Follow” and “Canons”

Mirroring - following the movements of a partner

Ball Rolling - giving just the right speed and pace to reach your partner on the next downbeat

Sound Machine: set-up for a group vocal improvisation

Ball Passing with Music - using music to regulate motion with an object

A Self-organizing Scale - collectively forming a scale where each one has their own pitch

Thinking and Sensing: Word Association with Hand-squeezing

Untying The Knot - group intelligence; working out a problem that involves everyone

Follow the Leader - an easy way to begin group improvisation

Wall - addressing the approach of fear

Crusis, metacrusis and anacrusis: Continuity and momentum in music

SoundWalks - environment as ‘score’

How to Make a Rhythm: 70 Permutations of 11112222

DISPLACEMENT (Rhythmic Displacement)

*Introductory note to teachers interested in using this material

There are many exercises presented here along with rationales and strategies for their use and presentation. For the most part, they are intended for music teachers and those who lead music workshops. They were all developed during my university teaching, so some of them may need modification for use with younger people.

While both games and exercises can address the same needs, children’s games, for example, tend to be more one-dimensional in the sense that they don’t necessarily present graduated levels of nuance and difficulty leading toward a predetermined goal. Once you learn the game, you can keep improving your proficiency, but it’s often more or less the same each time.

For me, though, the main difference between an exercise and a game lies mostly in how it is presented. Exercises are usually intended to develop increasingly nuanced technical, perceptual or theoretical skills, and most of the exercises on this website are also intended to develop musical attention. Games are not typically used in pursuit of a specific educational agenda.

Yet, almost all games do have great educational value, so turning them into exercises is an easy option for the creative teacher. There’s a loose parallel in the instrumental and vocal literature, where you can find many piano études which are essentially rudimentary technical studies (e.g., Czerny), while many others rise to the level of concert repertoire (e.g, Liszt and Chopin). I try to highlight the most important benefits of each exercise, because the purposes they might serve are not so easily named as, for example, “diatonic parallel sixths,” or, as Debussy’s subtitle of his Étude #9: “Pour les notes répétées.”

While some of the following games and exercises are intended as a first exposure to key ideas and challenges, many of them are intended to address the development of specific skills. The latter are usually presented with graduated materials to accommodate different levels of accomplishment, and you may see hyperlinks leading another location on the website where a more robust form of the skills is elaborated.

Where it seems useful, I try to offer some insights I’ve gleaned about the benefits of different presentation styles for each exercise. And lastly, I’ve tried to indicate possible diagnostic uses of some of the exercises that might not be evident to a new teacher. I have often found the diagnostic applications to be as important as the skills which are the main benefits of working with the material. Teachers often have to wait for the results of a test to see how the students are doing; my hope is that you find many diagnostic applications of these materials, so you have ongoing feedback as to the needs of your students.

Lastly, I have generally avoided any indication of specific ‘outcomes.’ A worthwhile exercise, for me, is more than a functional, outcome-driven activity. It should open up the students’ sense of exploration and awaken their curiosity about the elements of music and about interacting with other musicians. Too often the potential flowering of our work is prematurely curtailed by the assumptions and misconceptions which we may inadvertently bring to an activity. So the outcomes will naturally be different for different teachers, different students and certainly in different situations. Some teachers may use an exercise mainly for its diagnostic potential while others will use it to assist in the achievement of a particular skill-set. There are many ways to use a good exercise. Although not every exercise can address all three of our main teaching concerns, I hope that many of these exercises can assist the development of the sensitivity and intelligence of the body, the mind, and the intelligence of feeling.

RHYTHM & MOVEMENT

Pedagogical comment:

Jacques Dalcroze was an excellent and innovative music educator, and he highlighted the importance of incorporating full body movement, particularly in the teaching of rhythm. Long before I met with his ideas (and having enjoyed years of involvement with various traditions of folk dance), I became aware that, without literal movement of the body, rhythmic perception and execution will be weaker, less available and, because it will not be as deeply internalized, it will be less reliable. And since rhythmic flow is an ineluctable component of all musical performance, I feel that it is vital to include the education of the body.

For the most part, this rhythmic material is intended to be done with hand-clapping, vocalizing, miscellaneous and home-made instruments. [The problems that arise from a reliance on hand-clapping for learning rhythmic skills are written about in another website location.]The material presented here is intended for use without any specific level of instrumental proficiency.

§ § §

Movement games and exercises

~ in a circle ~

§ §

Exercise: Playing for The One

Listening through moving

This is a great way to get your students to listen more attentively to all the various qualities of music and performance. It will help them to become aware of the interaction between tempo, meter, texture, form, articulation, and so on.

The Set-up

Invite the people in your group to move around the room in any way they like. They should avoid moving all together in a circle, and they should follow their own path through the space … but trying not to bump into anyone else. They can find any tempo and any character that suits their mood. They could move like an animal or a machine, or they can move like a cartoon character or anything they can imagine. BUT: it is important that they try to stick with it while they listen to the music played by the leader. Their instruction is to listen but to try NOT to be influenced by the music at all. That is not easy because once we are listening it is hard not to imitate the qualities of the music.

The musician has the hardest job here.

After observing all the different movements and qualities among the individuals in the group, the musician chooses only one person, and they try to mirror that person’s movement in their music. Their aim is to correspond as closely as possible to that one person: to their tempo, their mood, their phrasing, the articulation of their limbs, and so on. All the movers are listening, in order to determine if the music is really accompanying them. They ask themselves: Does the music really “go” with my movement? Is the musician playing for me?

If they feel that the music is not supporting their movement they can quietly sit down to watch the others who are still moving. While they observe and listen, they can each try to figure out for whom the musician is playing. Ideally, only one person will be left moving, at which point the musician reveals who they were playing for. If it was the last one moving, then they can be asked to continue their movement while everyone joins in, trying to move in the same quality as the one who was chosen.

Contingencies:

If that last mover was not actually the musician’s choice, then there are several options for continuing the exercise. The leader can reveal who they were accompanying and ask that person to move again as they had been moving with everyone then invited to move along with that quality of movement. At this point a new round can begin with everyone moving in a different way. The leader could decide to let someone else be the musician. If there are no instrumentalists up to the task, someone can use their voice, which is a wonderful way to run this exercise.

If, by the time most of the participants are sitting and watching, there are two or more people still moving, the leader can invite those who are sitting out to say who whose movement seems best supported by the music. Who do they think the musician chose to accompany? They might all be invited to imitate the movement of each of the remaining movers in turn, in order to sense in their body which one has the best correspondence to the music. Or, they could be invited to listen to the same music while moving in someone else’s style. Does the music fit this movement? This work provides an excellent segue into a discussion about the individual parameters of musical texture and the ways in which they interact.

Exercise: Morphing and passing

Categories: Icebreaker / Modeling /

A number of the following games and exercises will serve very well as icebreakers as well as providing new experiences for both musicianship and improvisation.

The Play:

With everyone standing in a circle, one person (A) volunteers to begin by creating a repeating movement together with a vocal sound. It is best if it is totally spontaneous, but some participants may need a few moments to find something they like. When they have settled on it, they take their sound/movement into and around the circle. They should try to make eye contact with people as they bring their sound/movement around the circle.

*They then choose someone else to continue the sound/movement. They do this by standing in front of that person (B), trying to make their sound/movement as clear (and as enticing) as possible. That person (B) then begins to mimic the sound/movement in sync with the originator.

*The originator (A) should not walk away until they are satisfied that (B) has got it all: the movement, the sound, the attitude and energy.

*Person (B) then takes the sound/movement into the center and around the circle and, while repeating it, they gradually morph both the sound and movement until it becomes something different.

*Finally, they choose someone (C) to mimic their sound/movement, and they persist in their own performance until they feel that it has been successfully transmitted to the new person. And so it continues.

You will undoubtedly find many possible variations on this principle of passing a movement and sound. Have fun!

- - - - - - - - - - - -

“Razzberries”

Categories: Icebreaker / Modelling / Passing / Sound-Movement

Explanation:

Although razzing has connotations of teasing and taunting, razz is used here to mean a funny or provocative vocal sound made to another person. It can also include gestures and other bodily movements. Despite the origin of the word ‘razz,’ it should not be delivered in a nasty or mocking spirit.

This is a great icebreaker for a new group, and it’s also a good barometer by which the spirit of an ongoing group can be measured. ‘Mistakes’ occur frequently and they all invariably evoke good-hearted laughter. Razzberries touches on several other important dynamics needed for a good learning environment.

The Play:

With everyone standing in a circle, one person (A) ’razzes’ the one on their right. That person (B) first gives the identical razz back to (A) on their left. Then (B) turns to their right and gives a different razz to the person (C) on their right. (C) turns to the left and gives the same razz back to (B) … and then, turning to their right, (C) gives a new razz to (D). And it keeps going around in that manner. In situations where there is a fear of spreading germs, the game can be played with mouth-closed sounds or even with gestures only, that is, without making sounds.

Pedagogical rationale (What’s the point of doing this?)

It is a fun exercise and usually gets pretty silly and often quite uproarious. It is almost impossible for anyone to resist the lunacy that usually ensues. It puts everyone on an equal footing: those who are already known to be more proficient musicians than the others are taken to the same level as everyone else; there’s a mutual recognition that sounds and movements are really fun. We become like kids again (because we never really abandoned that stage). It’s a bit like entering a “beginner’s mind.”

Diagnostics:

It is also an important *diagnostic tool for a leader who is able to see which parts of the participants’ bodies are really alive and those parts which do not participate; and it is the same with the vocal sounds. Some will resist trying to find a different ‘voice,’ while others will immediately avoid using their natural voice. Some people cannot find a coarse, throaty sound; others cannot find a playful falsetto. Some people do not engage their face at all. Some use their hands but not their fingers or their torso. Some cannot (or do not want to) make ‘ugly’ sounds, and it becomes clear that one of our potential obstacles is our self-image. Do the participants with relatively small bodies ever try to create a big sound and vice-versa? [This exercise pairs well with Wall.]

With attentive observation, the leader can glean a great deal of information relevant to each student’s overall approach to music-making, and it can be used to better focus their teaching. The observations gleaned from this and other activities, are not intended as material for analysis, but they may reveal insights relevant for teaching music performance and improvisation.

* In my own teaching, “diagnostic” tools are not formal, analytical tools; they are only meant to serve as lenses through which the teacher can better observe, identify, and understand something about their students’ capacities and behaviours. Sometimes the exercise is itself a means of addressing their lack, but it is at least a way for the teacher to identify a student’s needs.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Word association

Categories: Language / Quick reaction

Rationale for the exercise:

Among other things, the improvising musician needs to be very responsive to the moment—to the immediate effects of impressions arising in them from both external and internal influences. This game can help foster that willingness in many participants.

The Play:

This can be played with only two people or a group. The group should be seated in a circle or such that there is a clear order to the responses. One person begins by saying a word that pops into their mind and the next person then says the first word that immediately comes to them by association. And so it continues. There is no set rhythm to this; each person speaks as soon as they have a contribution. Most participants will have experienced this before so you can try one of the variations below.

Considerations:

The rapidity of associations can be very stimulating and, because there are no ‘wrong’ answers, it can free people to participate, especially those who may be shy or hesitant to reveal what they consider to be their lack of skill. But some people do not like being put on the spot, even in a game-like setting, so the leader might suggest that anyone can say something like “pass” which allows them to divert the pressure while still participating. Or there can be another response such as “Back!” in which case the person who just gave a word now has to come up with a new association. Another way to relieve any perceived pressure, while still keeping everyone in the game, is to designate a signal by which anyone can indicate that they are starting a new word with no association at all. (What will be interesting is to review, after the exercise, to see if in fact the new word was really new or just an association that the speaker didn’t feel was ‘right.’)

Variation 1: The Second Association:

This variation is a bit tricky to manage. When presented with a word, instead of voicing your first association, you can hold it for a moment until a second association comes to mind, and then you say THAT word. The idea is not to pause so long that you think of many different associations. You choose the first new one that comes to mind.

Rationale for Variations 1:

Musicians often react to what they’ve just played or what they’ve just heard, and they play the first thing that occurs to them. This is one way that players succumb to mental or physical habits without realizing it. This exercise may encourage you to see the advantages of holding off for a moment to see what else comes to mind or hands. This second association may feel totally unrelated because we don’t know how the person got there. You yourself might not know either. But it is useful for the everyone to realize that we have to take the responses of others without judgment; our inner worlds are hidden.

Variation 2:

One way to help steer clear of the most habituated responses is by either expanding or limiting the scope of associations. Limiting the scope can be done by establishing ‘rules’ for proceeding. One example might be that the next word must have a specified relationship to the previous one. For example, it must begin with the third letter of the previous word. Or the next association should have the same rhythm or the same number of syllables. A sensory-based association might involve color, texture, weight, aroma, or it could be based on the actual sound of the word such as rhyming. It could be based on the color of the object (if there is one) or the season or time of day. By directing the attention to a given category, it can have the effect of redirecting associations away from habituated patterns and toward a fresh response.

Example: While ‘tree’ might strongly associate with ‘swing’ or ‘branch,’ a direction from the leader to associate with color might influence someone say ‘traffic light’ (green) or ‘novice’ (being ‘green’) or ‘envy’. If the instruction was to associate with shape, the next association might be ‘prayer’ (outstretched arms) or ‘family’ (family tree).

Diagnostics:

Because this exercise is mostly intended as a preparation for improvisation, the stress is best placed on spontaneity. So the leader should take note of people who are clearly associating with a word which was voiced earlier in the circle, that is, they are not being responsive to the person speaking immediately before the one whose turn it is to speak. This can indicate several things but it essentially shows the way that our attention often ‘stops’ at a certain moment after which we no longer are actively attentive. We can become intrigued with a word for some reason or we get fixed on the word that we would have said at some earlier point, or we start thinking about it all. This ‘bump’ in our attention happens all the time—often in a gathering when, by the time I tell a story, the moment of relevance has actually passed. And sometimes it makes for what seem like strange non-sequiturs.

Rationale for the variations:

The suggestions are all quite germane to creativity and improvisation. Often the limiting factor for a player is the frame of reference to which they are habituated. I notice that some players get an idea fixed early in the improvisation which acts to filter out what is happening in the present moment and, on the other hand, some players are so occupied with the music they are playing, they cannot recall where they were even a half minute ago.

Thoughts and observations:

Creative improvisation is difficult to teach. We want to stimulate an immediacy of response in order to evoke authenticity and new experiences, but that very immediacy often steers us into habituated reactions. That conundrum is dealt with throughout this website. It’s tricky…

- - - - - - - - - - - -

#4 Circle Counting

Categories: Finding Your Count

This game/exercise has been in common practice for some time. My guess is that it might have originated as a theatre exercise.

The Set-up

Being seated in a circle works well for this exercise, but any random configuration is fine as long as the participants are ableto vkeep track of a clear sequence of people within the group.

The Play:

The group will count, one person at a time, up to the number of people in the group. So if there are 15 people, the participants will count from 1 to 15 (repeatedly), with each person speaking individually and only once per cycle. There is no need to fix a general tempo or a rhythm and, while the counting should maintain the natural ordinal numbers, the order of speaking is improvised. As each person says the next number, they must also clap simultaneously with the number.

So someone will clap and also say “One!” at the same time. The next person will clap while saying “Two!” Both the clap and the vocalizing of the number are important. If either the clap or the number is missing, the sequence is invalidated and the group begins again from “One!” (Anyone may begin.)] It will continue until all fifteen people have said a number while clapping.

*If they forget to clap, the exercise begins all over again from “One!”

*If two people clap or speak at the same time (for example, if two people say “eight” simultaneously) the group begins again at the beginning with someone counting, “One!”) No one takes two numbers so each participant will speak and clap only once.

Rationale:

Musicians need to sense the immense number of ‘moments’ that potentially exist between any two beats or sub-beats or phrases. This is necessary when playing very quickly flowing music but even more so when playing music in a slow tempo or music with rubato. It’s indispensable when learning to “place” a note for interpretive emphasis. (Of course, many teachers may not be working with students at a level where this is a need.) We also confront this need when an ensemble is required to enter together after a substantial rest. When, exactly, is it the right time? A surprising amount of anticipatory tension can develop before each new number in this game/exercise.

Moments just go whizzing by …

After a couple of experiences where two or three people all shout out the same number, that is, when another person ‘takes’ the number they each intended to say, everyone becomes increasingly sensitized to the silence before each new number is called. You want to say it but you’re not sure that someone else will speak for it—even just before you do. You wait a few moments in excited anticipation, so as not to collide with another person’s moment. So the silence between numbers can be quite highly charged. You want to declare it and shout the number and clap, but you’re waiting to see if someone else takes it. Then you shout the number but forget to clap, or you clap forgetting to say the number. Or you decide to shout your number (let’s say, eight) immediately after you hear ‘seven.” And without waiting a microsecond you say “Eight” … but simultaneously as someone else has the same strategy.

So everyone begins to feel the palpable passage of almost innumerable moments of time between the numbers—something like the falling of thousands of tiny grains of sand in an hourglass. What formerly seemed like only a “moment” begins to expand into a plethora of moments. You may not have been aware of this before playing this game. This expansion of our time-sense is the kind of impression that an artist really needs.

This exercise can make us aware of the need to ‘speed up’ our perception of time flow by appreciating the expanse of musical terrain between the notes. We often imagine, for example, that playing in a slow tempo is easier because there’s not as much going on. However, slow tempos often require the player to “go faster” inside, that is, with a finer granularity, in order to be on time, or to play on the ‘back’ of the beat, or to execute a tasteful rubato.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Circle Clap

Categories: Rhythmic perception / Icebreaker

Back to the T.O.C.

Locating yourself in the flow

The general idea of this next series of exercises is to develop a clear sense of your musical place within an ongoing cycle. As musicians, we need to be able to ‘locate’ ourselves with or without visual cues. There are many ways to engage with this and there are many more variants than will be presented here. For teaching purposes, I suggest that rather than inventing new variants, watch your students and figure out what they need.

Rationale

There are many situations in which performing musicians can lose their place in an ongoing flow. For example, vocalists may lose track of the 32-measure break during a complex solo, particularly a drum solo. Heavily accented shots or syncopated phrases can be mistaken for a downbeat and can disrupt the sense of where you are in the cycle. This exercise may help strengthen the sense of rhythmic cycles and your place within them.

Pedagogical strategy

So these exercises each have, as their M.O., disruptive or challenging elements that dislodge the sense of one’s location in the ongoing cycle. Specific strategies for practice will be suggested.

§ § §

Circle Clap ~ a

Developing Peripheral Vision

The Set-up

At a slow or moderate tempo, participants begin clapping in turn around a circle in a steady pulse. The tempo should be slow enough that no one gets lost.

The leader will determine the direction of the passing clap and will begin with the first clap or designate someone else to begin. As the clap begins to move around the circle, try looking straight ahead across the circle, getting your cue from peripheral vision. At the beginning, it’s okay if you need to turn your head to see where the clap is so you’re not caught off-guard. However, it’s good work to try looking only with your peripheral vision.

Pedagogical rationale:

In our normal activities we often need to incorporate a global focus as well as a narrowly directed focus. In many musical situations, it may not be possible or wise to maintain an exclusively narrow focus. For example, musicians using a notated score must learn to keep both the score and their instrument in their field of vision. This is particularly the case for keyboardists, percussionists, church organists, who are already obliged to see the entire expanse of their instrument(s) as well as the specific places they need to touch. Orchestral musicians must attend to both the conductor as well as their score; musicians accompanying dance or theatre must learn to develop their peripheral vision (as well as peripheral attention.) This exercise can develop your confidence to trust your peripheral vision and to expand your attention.

§ § §

Circle Clap ~ b

As above, but without relying on visual cues

Trusting our ears, not only our eyes

The leader sets a tempo and then begins the exercise with a clap which is then passed in a steady pulse to each member of the circle. The tempo should be such that each person is able to participate with confidence and help to maintain a steady tempo. After going around the circle a few times and becoming familiar with each person’s sound, you can try to keep the sound traveling around without looking at anyone. Relying exclusively on listening cues is difficult but it is easiest if each person’s sound is somewhat distinct from the others. This can be done by using sounds other than clapping, such as vocalizations or with pitched percussion instruments (such as Boomwhackers). The idea is to see if the succession of sounds can itself serve as cue to locate one’s spot in the cycle. Students can try closing their eyes for a short time and perhaps they might try keeping the sound going around without looking at all.

§ § §

Circle Clap ~ c

with gradual acceleration & strategic visual cueing

The Set-up

This exercise should be set up as in Circle Clap ~ a, b, and c. So, again, the leader establishes a comfortably slow tempo before beginning the circular movement.

Controlled Acceleration

Begin the circular passing of the clap at a slow tempo. Only after two or three times around the circle—when everyone is quite relaxed and the tempo is really steady—should there be an instruction to let the pace quicken. No one should intentionally try to speed up the pace of the clapping but rather allow it to accelerate. The tempo should ideally increase so gradually, that a person entering the room would not immediately realize that it’s accelerating. (When someone intentionally increases the tempo, it will almost always take the next person by surprise resulting in a bump in the tempo that will disrupt the continuity. It will almost inevitably result in a loss of the beat and the breaking of the movement around the circle. The group will mostly likely have to begin again.)

See how fast the clap can proceed around the circle before it disintegrates. It will fall apart, but try several times to see how fast it can go. Can the group reach six claps per second or faster?

Possible discussion:

Why do we keep losing the continuity? How can we make it go faster without losing the flow?

Performance Strategy 1 (for going really fast around the circle):

* Here are two remarkably effective methods. First, count the number of people in the whole circle and, with everyone imagining that they are the beginning of the circle—that is, that they are “number one”—we all count to that number and clap when we say the number “One.” So if there are 8 people, we will each count from one to eight and clap when we count “One.” The group can easily accelerate the counting to a very fast tempo, with everyone clapping at the same time (because everybody is “One”—a sort of “Buddhist” exercise). This should be very easy to do.

* The next step is that each person in the circle counts the same way [counting to the number of people in the circle, and clapping when they say “one''), but they each stagger their first clap so that they start their clapping one after another. (So I would clap and start counting when the person before me is counting “2.”) If each person enters in succession and counts to the same number (as there are people in the circle), it should be possible to do this with eyes closed. It may be more difficult to visualize this than to just do it, but there are some illustrations below which may help. And after feeling secure with that, the group could try incorporating the acceleration. Remarkably, it works very well … but it does take some practice.

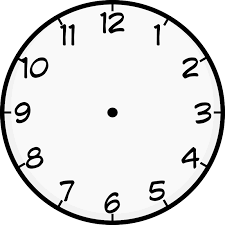

If you need to visualize it, look at the two illustrations that follow the section “Performance Strategy 2” (with blue dots and with a clock face):

Example:

There are 9 people playing: Alys, Bob, Casey, Deanna, Ed, Flora, Germaine, Hunter, Isabelle. Before beginning the clapping around the circle, Alys will set up a slow tempo, allowing enough time for everyone to sense it. At some point, she’ll start the movement by clapping and saying, “One!” As she continues counting inwardly, she notes that Bob is 2, Casey is 3, Deanna is 4, Ed is 5, Flora is 6 and Germaine is 7.

On the next beat after after Alys, Bob claps and says “One,” because he is initiating a new cycle. (Alys will sense him as “two,” so she must maintain focus on her own counting.) As Bob continues silently counting, he understands that Casey is will also count himself as, “One!” Each successive person counts themselves as “one,” so each player will be having the same internal experience. [This is essentially the technique used by performers of certain minimalist “pattern” music.]

Performance strategy 2:

Here’s one way to do it that is actually quite relaxed.

If you are depending on looking at each person, it can be difficult and even dizzying to watch each person take their turn clapping, especially when the tempo increases. The easiest way to do this is by grouping the other participants. So if there are, in this example, nine people in the circle, you can divide them into three groups of three. Then, counting yourself as ‘one,’ look to see who will be the next people to clap and take note of the people whose count will be “4” and “7.” When doing the exercise, you only have to quickly spot them; you don't have to take the time to mentally name them. Those two people plus yourself make three relaxed landmarks for counting to nine: “One, 2, 3, Four, 5, 6, Seven, 8, 9.” Alys would see: “Alys, 2, 3, Deanna, 2, 3, Germaine, 2, 3.” I am Casey, so I would count: “Me, 2, 3, Flora, 2, 3, Isabelle, 2, 3.” And this can be easily sensed musically as three groups of three—like 9/8 time. Make a visual note of who they are so you only need to ‘spot’ those two as the clap goes around the circle. Just remember that you only need to keep track of the two people whose location helps you to keep count. (If there are 12 people, you can group them into 4 groups of 3 or 3 groups of 4. If there are 13 people in the group, you can have fun figuring out what is the most comfortable grouping: 4+4+2+3 or 3+3+3+4, etc.)

The images below may help you visualize what was just described. There are no numbers in the image because any blue dot could be you.

If there are 12 people, you can even imagine a clock face (see below). You could divide the circle into three groups of four, with you as number 1: (#1-Casey, #5-Germaine, #9-Katherine) or four groups of three people (#1-Casey, #4-Flora, #7-Isabelle and #10-Larry). Again, if the number of people in the group is not divisible into equal groups, like 7 or 13, you can experiment and learn which groupings will be easiest for you to count.

Rationale for the exercise:

So, regardless of the number of players, you can use your spatial sensibility to keep track of the count. In other words, it is possible to keep accurate count without ‘counting’ at all. This is exactly what orchestral players do when they follow the conductor’s baton. An experienced musician has already internalized a four-beat grouping but the movement of the baton is still very helpful. They know the “shape” of a four-count or a five-count, so the movement of the baton through the shape does the counting, and it is just as reliable as if the conductor were counting aloud. Musicians from other cultures have a long tradition of physical and spatial counting, where gestures of the arm, hand and fingers are used to do the counting. And musicians also commonly use their own physical cues to engage in non-intellectual, non-verbal counting: subtle leaning of the torso; pointing their foot, or sensing the four directions in the room. The intelligence of the body is perhaps our most reliable ally in matters of rhythm and perception of time-flow.

[You can find a greater development of these ideas elsewhere on this website: Terry Riley—Comping Exercise; Fifty-fours, etc.]

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Finding My Space - a

Change this subtitle….

Pedagogical Comment:

There are a number of games and exercises in this file (and on the website) that aim to cultivate the perception of “rests” not as a cessation of music, or as the absence of notes, but rather as an active presence--an integral part of the musical fabric. Just as a button hole is not simply a place where there is no shirt, a rest must be actively ‘played.’

The Play:

In this exercise, each person gets to clap only once. The person who begins, claps their hands and simultaneously calls out, “One!” The next person to clap, clearly calls out, “Two!” This continues until each person has had a chance to clap and say their number. But if they say their number as someone else is also calling the same number, the group must begin again from number One. Anyone can begin. If everyone in the group has had a turn, they can try to go through the group again, with another person starting with, “One!” If the group goes through more than one cycle, then again each person has only one clap in each cycle. If you clap without calling your number or if you call your number and forget to clap, the group must begin again at the beginning … and anyone can begin with “One.”

This sounds easy and sometimes it does go very smoothly, but it is surprising how difficult it can be to get through everyone without having to begin again (and again).

Some advice to teachers:

At first, no one expects to ‘collide’ with anyone else. We generally think that it will be easy to find a space for our number-and-clap but, as the game progresses, we are usually quite amazed how often someone chooses the very same moment to say their number and clap. The game often slows down as people really try to find a moment when their own clap and number will be unique with no collisions. So we are all quite surprised that, even after a long pause, just when you feel that no one is going to clap, two or three people will clap and say the same number at the same time.

And so the passing time becomes highly charged. There seems to be an infinite number of passing moments—moments of “Now!”— and yet we often manifest the identical impulse as our fellow musicians. This awakens some people to the aliveness of the passing time. The leader might find ways to point out that this energetic ‘charge’ is what is needed in their performance practice.

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Finding My Space - b

Finding a point of emptiness (silence) within an ongoing rhythm cycle

Rather than the Absence of something, rests may better perceived as the Presence of nothing

~best to do with between 5 and 20 people~

Rationale

This is a group exercise which involves finding an unoccupied beat in an ongoing rhythmic cycle and being able to stick with it while the cycle repeats. It is based on the reification of musical silences (rests), that is, making rest an active, palpable experience. Younger musicians, and those who do not perform, often regard rests quite passively, as if they were ‘dead air’ to be dutifully counted until it’s time for the next notes to be sounded. This exercise aims to enhance the appreciation and value of rests, making them an active presence rather than an absence.

There are many ways to organize this exercise, and the creative teacher can make many variations to keep it fresh for the students. And the students can, as with almost all the other exercises here, be given an invitation to come up with their own variants.

How to play:

The leader begins by striking a single definitive sound which begins a rhythmic cycle and which repeatedly re-initiates each new cycle. The leader, and/or the group, can count aloud, softly at first (and then only inwardly), from “one” up to the total number of participants. (So the count will go to 13 if there are 13 people playing.) After the leader begins the cycle, they nod to any other person, who then chooses any unoccupied count on which to make their sound. That means, they can play on any count where no one is playing. So if they choose to play on count “10” they will play on that count each time it comes around again.

Only when that person feels comfortable and stable on their count do they give a nod to someone else in the circle, who then also chooses any unoccupied beat to play, and they play on that same beat during each subsequent cycle. The participants can continue counting to help maintain their place in the cycle, or they can begin to trust the sequence of sounds to tell them when it’s their turn.

Gradually more and more beats are chosen and, as they become occupied by sounds, it becomes more difficult for the last few people to find an empty beat. This is a particularly interesting part of the exercise, because the players must deal with the increasingly difficult task of finding an available (unoccupied) beat. Whereas we typically listen to music mainly for the sounds, here, the players find themselves actively listening for the silences. The result is a kind of ‘reification’ of the silent beats, where the ‘rests’ become as active as the sounds. “Nothing” becomes another kind of “something.”

Variations:

There are many ways to make this exercise more challenging as well as more musical. The leader can suggest that, in addition to your chosen beat, you also articulate the following beat; or the next two; or skip one beat before again striking your note; and so on. Or, in place of simply articulating their chosen beat, they play a motif of their own choosing or chosen by the leader. Or they can improvise, regarding their chosen beat as the beginning of their own cycle. Or, at a cue, everyone changes from percussion to short vocal sounds … then loud ones … and so on.

You can make eye contact with someone in the group and, while maintaining your place, make eye contact with someone else and silently agree to switch places with them—i.e., they take your beat and you take theirs; at a cue, everyone changes to a vocal sound; etc.

Rationale:

There are a few things that can be learned from this game/exercise. One lesson is that it is not so easy to keep your place in an ongoing cycle when you have a relatively small contribution to an ongoing flow. This is a bit like the skill required in many traditional (and contemporary) styles and ensembles, and your students would probably love to see and hear a few of these.

*Interlocking parts in Steve Reich’s Clapping Music

*Klangfarbenmelodie in Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra

Another point—very important for playing standard solo and ensemble repertoire—is that our typical musical training (especially in the beginning years) tends to regard rests as passive moments in the music. It is where many students begin to believe that you do “nothing.” (Isn’t that why they’re called “rests?”) Consequently, musicians (especially young ones) do not feel or sense the ongoing flow through those moments of ‘emptiness.’ Therefore they tend to be moments of hiatus in the compositional flow.

In this exercise, it becomes increasingly difficult for each newly added person to find an unoccupied beat, and they really have to listen attentively to find it. We typically do not attend to these empty moments with the same quality of musical attention that we give to the beats with sounds. Consequently, students often ‘cheat’ the rests, failing to give them the fullness of time that they require, and the tempo often lurches forward.

[Note: In some musical cultures, such as in Carnatic music from the south of India, the performer physically taps, claps or conducts the beat as they perform on stage (assuming that one hand is unoccupied). If they do not keep a physical count, someone in the ensemble will do so. And they don’t simply keep an undifferentiated beat, but they rather identify the ordinal number of the beat through special formalized gestures. Just as a conductor of Western orchestral music can show, through gesture, which beat is being played (down, left, right, up),

some cultures can show quite precisely where they are, even in a cycle of as many as 13 or 22 beats. Here is a common shape for showing an 8-beat cycle in Carnatic music. Adi Tala. This is not understood to be a crutch for a weak musician, nor is it regarded as any kind of ‘cheating.’ It is useful for all the musicians on stage and even the audience, because it helps everyone keep in touch with the complexities of long metric cycles and highly syncopated patterns.]

Categories: Rhythmic perception / Reification of silence

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The Clapping Game

~ Looking for Nothing–2 ~

(composed and published by Toronto percussionist Bob Becker)

Background

This exercise/game is a good companion to the “Unison Exercise.” Both exercises invite you to assess a musical value in “real time,” that is, without stopping to think about it. The Clapping Game is actually a published composition which is presented in the form of a game. It is a good exercise that serves several purposes, and it gives the teacher an opportunity to observe their students’ problems with rhythm and with musical attention. Therefore it can be readily used as a kind of diagnostic exercise. (I no longer have the original instructions so these are my own reconstruction.)

The Play: Quick Description of Game Play (a shortened version for younger people):

The game is played with a partner. You each choose your own number from one to six and you don’t tell it to your partner. Once you’ve chosen a number, you both begin clapping together at the same time and at the same speed. Each clap gets one count. When you reach your number you leave one beat silent and then you begin again, counting from “one” up to your chosen number, and again you leave one beat silent at the end of your phrase. The game play continues that way until you hear the moment when you both play your silent beat at the same time (on the same beat), and then you try to STOP before you clap again! The game is about the ability to recognize the moment of a common silence and to respond by stopping. (Stopping “on time” can sometimes be as difficult as playing on time.)

This activity gives a much more dynamic experience if played back to back or with the eyes closed.

Detailed Description of Game Play (for older kids and adults)

Each player chooses a number from one to six and neither tells their partner which number they have chosen. Both players will begin to clap together, starting at the same time and in the same tempo. You each clap up to your chosen number, then leave one beat silent, and then repeat the phrase including the one beat of silence. You continue this until you reach a common silence. Without any break in the rhythm, you each choose a new number (between 1 and 6) and continue the game play with that new number. You continue until your phrases align again and you hear another common silence. Again, you again each choose a new number and continue the game play.

If you have chosen a new phrase and your very first silence is in common with your partner, it means that you have both chosen the same number. That is almost the end of the game but first you play a rhythmic cadence—a coda. The coda is simply to play that last phrase together another two times, so you’ve played it three times in total. And THAT is the end of the game. Bravo!

A demonstration example

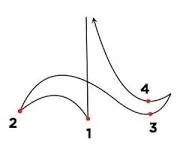

If, for example, Player #1 chooses “3,” she claps her hands for three successive beats and remains silent on the fourth beat. Then they repeat the whole 4-beat phrase: clapping three times plus a one-beat pause. If their partner (Player #2) chooses the number “4”, he will clap four times, leave one beat silent, and then he will repeat that whole 5-beat phrase. The results of player #1 and #2 are visualized below.

#1 Clap Clap Clap rest Clap Clap Clap rest … … etc.

#2 Clap Clap Clap Clap rest Clap Clap Clap Clap rest … … etc.

It is fun for the players to try to notice that the silences shift around; they either seem to get further apart or closer together but, sooner or later, both players will rest on the same beat. When this occurs, both musicians change their number and, without missing a beat, they keep the game going: they clap starting from ‘one’ and count to their new number, still adding one beat ‘rest’ before they repeat the new phrase. It is important that they do this without skipping any beats so the tempo remains steady. The graphic image below is laid out like a musical score: one part above the other. In the demonstration example below, Musician #1 has chosen 3 and Musician #2 has chosen 4. (The “C” represents a “clap” and the “r” represents a rest.) It is easy to see that the rests will eventually align, which means they occur at the same time.

#1|| C C C r C C C r C C C r C C C r C C C r

#2|| C C C C r C C C C r C C C C r C C C C r

The teacher can make a stronger graphic image by using large paper or objects such as playing cards, coins or anything that will help young students see that the silence is also a musical action. In this example, the players can see that, by the time the silences align, player #1 has played four silences while player #2 has played only three. For older students, the teacher can introduce the idea of “cross-rhythms,’ but that’s explored in more detail elsewhere on the website. Meanwhile the teacher may choose to say something to the effect that the players don’t ‘rest’ on the silent beats (shown as ‘r’) but that they “play” the rest or the silence. When introducing this exercise, the rests can be played as active gestures on the thigh or on a pillow. Those silences are active experiences and they eventually need to become a palpable experience without striking anything at all.

Below there’s an illustration of the beginning phrases of a game. Player #1 has chosen a phrase of ‘3’ and Player #2 has chosen a phrase of ‘4’.

#1|| C C C * C C C * C C C * C C C * C C C *

#2|| C C C C * C C C C * C C C C * C C C C *

After Player 1 claps four repetitions of their phrase of 3 (3 claps plus 1 rest), the last rest aligns with the last rest of Player 2, who has clapped three repetitions of their phrase of 4 (4 claps plus one rest). That common silence is the cue for both players to change their number and continue without any hesitation. When their silences converge, #1 has switched to a 2-beat phrase while player #2 has switched to a 3-beat phrase.

#1|| C C * C C * C C * C C * C C * Since the rests align, they must both change their phrase

#2|| C C C * C C C * C C C * C C C * Since the rests align, they must both change their phrase

= = = = = = = = = = = = =

Here is the same game-play written as numbers. Player 1 has chosen to clap three counts (plus a silence), and player 2 is clapping 4 counts (plus a silence).

#1|| 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 *

#2|| 1 2 3 4 * 1 2 3 4 * 1 2 3 4 * 1 2 3 4 *

Below, each phrase is numbered so you can see how many repetitions of phrase of #1 it takes to align with the phrase of #2. Sometimes ancillary material such as these images can be very help for some students. Others can be confused or put off. You just don’t know the scope of reactions until you try.

#1|| 1 2 3 * 2 C C * 3 C C * 4 C C * 5 C C * etcetera

#2|| 1 C C C * 2 C C C * 3 C C C * 4 C C C * etcetera

It is easy to see that the rests must eventually align, no matter which numbers the players choose*. But the experience of the rests coming at the same time gives the players a fresh experience of a “rest”—a new experience of musical silence. They begin to hear the silence not as the absence of a sound but as the PRESENCE of silence. So the student may begin to have a new impression of silence as an experience rather than the lack of one. For most students, this gives the experience of silence more ‘substance.’

On a personal note I can relate that I was so surprised when, after years of hearing Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, I was reading the score and was shocked to see that it begins with an eighth-rest. I always assumed that it began on the downbeat and, in fact, I always wondered why it appeared that orchestras entered a bit after the conductor’s initial downbeat. Looking at the score as an adult, it seems clear why the conductor makes such a dynamic gestures for that first bit of “nothing.” The orchestra has to really sense and inwardly “play” that first rest because, without it, the next notes cannot occupy their proper place in the phrase. And those five instrumental groups cannot enter exactly on time. (See the orchestral excerpt below. This is preceded by what I more or less heard as a young piano student. (So pedestrian!)

Opening of the Fifth Symphony, Opus 67

Beethoven’s symphony actually begins with ‘nothing’—a eighth-rest on the downbeat for the entire orchestra. And what I heard as a crusic phrase is actually anacrusic. A big revelation! As a youth, I always wondered why orchestras seemed to come in late…after the conductor’s downbeat!

Contingencies

*It occasionally happens in the playing of the Clapping Game that the silences never align, and this is due to one of two things. If the players choose the same number but do not begin together, their phrases will just keep cycling around, with its ‘head’ continually chasing its ‘tail.’ See the illustration below where both players have chosen “3” but player #2 accidentally begins two beats late. As you can see in the illustration below, the rests will never align.

#1|| 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 *

#2|| ? ? 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 * 1 2 3 *

Coda to the Clapping Game

The game can simply go on until there is a decision to stop but there is actually a published end to the game. At some point after a common silence and after both players have chosen a new number, their very first silence may align; it may be the same both both of them. Of course, this means that they both chose the same number. In that case, they go immediately to the Coda which ends the game. The Coda simply involves playing that last phrase two more times and then they stop.

So a complete game might look like this (just an example):

Player #1 is written above #2 as in a two-staff system of music:

Player #1|CCC*CCC*CCC*CCC*CCC*|CC*CC*CC*CC*|CCCCC*|

Player #2|CCCC*CCCC*CCCC*CCCC*|CCC*CCC*CCC*|C*C*C*|

Both parts continue but, with Player 1 choosing ‘3’ and Player 2 choosing 2, they quickly find a common silence. After that (after that first barline) you can see that they both choose ‘6’. Therefore the very first silence is the same for both players and so they go immediately into the coda. So they each play a phrase of 6 three times and the game is finished.

Player #1 | CCC*CCC*CCC*|CCCCCC*CCCCCC*CCCCCC*||

Player #2 | CC*CC*CC*CC*|CCCCCC*CCCCCC*CCCCCC*|| Game finished

Rationale:

There are a couple of things that can go wrong when playing this game, and they are all instructive of similer errors when playing ensemble music. People frequently count in an introduction but then begin playing in a different tempo. Sometimes, people will fail to give a clear gesture of preparation to begin. Or someone will count “one two three” and begin clapping on “Three,” while their partner was waiting to hear a concluding syllable: either “four” or “and.” It seems trivial but such mix-ups occur all the time even in professional chamber music. The Coda, which follows below, is very useful as a way of reminding students that the piece is not over when they hit the last note. They need to listen until the very end, especially how the music re-enters the silence from which the music arose. And they need to listen to the resonance of the music inside themselves. (One mentor suggested that a pianist should leave their hands on the keyboard until they themselves stopped listening. Dropping the hands while still holding the damper pedal often results in people thinking it’s finished, and they stop listening or even begin talking.)

For the teacher:

It may have been Mozart or Miles (or Satie or Debussy etc.) that said that the music is (also) in the space between the notes. Various composers and performers have made remarks supporting the idea that the music is more than the sounds that are played. Miles Davis said something related: "It's not the notes you play, it's the notes you don't play." And a well-known concert pianist, when responding to the question of what makes his interpretations so alive, was proud to say that he “plays” the rests.

It is wonderfully profound to try to understand what is meant in verse 11 of the Dao de Jing (Tao te Ching). Your students will probably fare better with a simplified wording but here is the ‘original.’

“(The usefulness of what has no substantive existence)

“The thirty spokes unite in the one hub; but it is on the empty space (for the axle), that the use of the wheel depends. Clay is fashioned into vessels; but it is on their hollowness, that their use depends. The door and windows are cut out (from the walls) to form an apartment; but it is on the empty space (within), that its use depends. Therefore, what has a (positive) existence serves for profitable adaptation, while the absence of those qualities serves for usefulness.”

[There are more streamlined translations on the web.]

- - - - - - - - - - - -

MORE CIRCLE GAMES AND EXERCISES

* Circle Clap Left-Right

Categories: Icebreaker / Physical passing

This quickly becomes a fast-moving game with lots of fun and laughter. It’s another great icebreaker and also a way to get a class or a group energized for work.

The Set-up

The group is formed in a circle with everyone facing the center and keeping their peripheral vision activate. One person begins by directing a clap to the person either on their right or left. (They then immediately face the center again.) The person who received the clap then quickly turns and directs a clap clearly to the person either on their left or right and again faces the centre of the circle. Everyone looks straight ahead into the center of the circle rather than visually following the clap. Each person tries to sense the movement of the clap coming toward them but without directing their gaze to follow it. It’s a bit difficult but it makes it quite exciting to realize that it’s possible to do, and it allows you to see the entire circle. Your clap can be directed in either direction around the circle and anyone can change it at any time. The game creates lots of energy.

Pedagogy:

The leaders will need to remind people that the clap can go in either direction and it should be passed to the next person while clearly facing them. That is, you give it directly TO them, so that there’s no ambiguity about the direction around the circle. This gives the participants some early practice in attending to their neighbour’s cue while still sensing the whole group—something useful no matter what kind of ensemble music they may eventually play, and whether or not there is a conductor or leader.

Variations:

Take a look at using hand-squeezing instead of clapping. The participants have to be much more rooted in sensation. Hand-squeezing

*

====================================================

Pace & Stride

General comment: Distinguishing pace from stride is not intuitive for most people but it is an important distinction for achieving the best outcomes in many activities such as sports, dance, in business, humour, learning situations, and so on. Pace and stride, even in this simple walking exercise, have several correlates in musical performance, involving parameters such as dynamics, forward momentum, rubato, etc.

Many teachers make use of analogies with areas seemingly unrelated to music, but the sensitivity and intelligence of the mind/body often digest those experiences in ways that can be surprisingly effective. They may become more available to integrate with what we have already learned. It seems that we may be better able to receive certain lessons which are learned indirectly, leaving us somehow free to creatively transfer that material to a dedicated musical domain. (A rationale for this exercise follows.)

Pace is the speed at which your steps follow each other, so it is related to time. Stride is the distance covered by each step, so it is more related to space.

Instruction 1: Keep your eyes looking forward and walk only in straight lines through the space. When you see that you’re about to collide with a wall or another person, turn in any direction and continue walking in a straight line. Now, without altering anything, bring your attention to the length of your stride, i.e., on the distance covered by each of your steps. … then, after some time …

Instruction 2: Now slow your pace (walk more slowly, but do not change your stride). Then after a time, try to quicken your pace but, again, without changing your stride. Keep walking only in a straight lines, keeping your eyes focused ahead, and don’t bump into anyone. If you see that you are going to collide with someone, keep going in a straight line but, and even while you take smaller or larger steps, try to maintain your pace. (So you can change the length of your stride while you maintain your speed of walking.)

Instruction 3: Now we can try switching the element that is fixed with the one that we can adjust. That is, now you can adjust the size of your steps (the stride) in order not to bump into anyone, while you try to maintain the same pace, that is, the speed of your walking.

Continegency: If the number of people moving the room is not practical for the exercise, you may have to change the conditions you present, so that the participants will be able to attend to both stride and pace in turn and also simultaneously.

Rationale:

It can be more difficult to distinguish pace and stride when you are in a room with other people moving all around you. You can become distracted and easily mix up stride and pace. (More importantly, there are similar confusions that we make in our practicing and performing of music.)

[For example, when we try to make our playing more exciting, we often play faster or louder when what might be needed is a more varied articulation. When feeling the need for more interesting sounds while improvising, we sometimes resort to using chords that have greater density instead of using fewer notes with wider spacing and more poignant intervals. And so on…]

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Friends and Enemies

General Comment: I probably got this exercise in a dance workshop given by Prof. Holly Small—a wonderful teacher and a long-time colleague at York University. It’s so much fun that people have no idea that they are learning anything at all!

The Set-up: Everyone begins to walk around the room on their own, at an easy pace and in a relaxed manner. It would be good to have a musician maintaining a calm, steady tempo. The walking could either be completely random or the leader could give directives concerning pace, stride, direction, saying hello or just looking at the eyes of people they pass, etc.

Instruction: At some point, the leader proposes that everyone secretly choose one person in the room to be their ‘friend.’ They subtly try to get closer to that person, trying to keep it hidden, i.e., not to make it obvious for example, by speeding up, or staring at them. So no one knows who has been chosen as a friend by anyone else. Of course, your chosen friend might well have chosen someone other than yourself as their friend.

After a time, the leader might suggest that everyone secretly adopt a second friend and everyone should try to get equally close to both of them. [This means that they’ll have to keep them both in their peripheral vision.] Again, everyone should avoid making it obvious by suddenly lurching toward their friends.

At the right time, the leader can propose that they keep their two friends but also choose one other person as their ‘enemy.’ Now they must try to keep the maximum possible distance from their enemy while also trying to get as close as possible to both of their friends. This is a challenge to one’s peripheral vision, and one’s ability to navigate between ‘attractions’ and ‘repulsions,’and it is especially tricky if you try to keep your chosen people secret.

Variations: (related to the exercise, “Pace vs. Stride”)

The players can move freely or they can be instructed not to change pace or stride, or to walk only in straight lines. The exercise could begin with the musician improvising a musical accompaniment in a comfortable walking tempo. As the music speeds up or slows down, everyone must stay in time with the music. Or by contrast, the players could be instructed to resist the changes in the tempo of the music and stick with the original tempo.

Rationale: (What might be learned from doing this exercise.)

Engagement with this exercise develops your peripheral vision and also your ability to move with an agenda but still controlling your speed and direction. The players try to balance their impulses of attraction (friends) and repulsion (enemies), that is, going away and going toward a goal point.

As with all these exercises, there are many variants possible, so the leader needs to prepare by visualizing how things might work out and deciding what they will look for.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

==================================================

Body Percussion

‘Orchestrating’ a rhythm with the body

Call-and-response rhythms are an excellent exercise format for musicianship work. It helps develop listening skills and short-term memory, and it can be parlayed easily into notation work (learning to quickly jot down what was heard), and creative work (applying musical values to the rhythms). Clapping is commonly used for teaching throughout the world because it’s simple: everyone arrives with their ‘instruments’ attached to the end of their arms. The main drawback of clapping is that distinctions in duration cannot be conveyed with the uniformly short duration of a clapping sound. Students invariably are misled by patterns with mixed durations, because distinctions in durations are not readily audible with only the short, uniform sounds made by clapping. Further, some students cannot absorb the rhythmic shape of patterns, even with several repetitions, because they are not able to distinguish the beginning of the pattern.

To repeat … Since clapping produces very short and relatively uniform sounds, every clap may sound to some people like the beginning of a phrase and, as a result, they cannot parse the grammar of the phrase. In that case, it’s important to use different sounds to help convey the impression of shape. However, rhythmic shape can be conveyed by sounds make with different parts of the body: abdomen, thigh, cheeks, top of the head, and, of course, foot tapping and stomping. The hands can find a wide palette of sounds by striking nearby surfaces (floor, table top, etc.).

next section is in wrong place!! fix by moving

Patterns and Rhythms

These are not standard terminology, and you can call them as you wish, but I believe it’s useful (for the students and for the teacher) to make a distinction between a rhythmic continuity which is characterized mainly by differences in duration and one which has clear and integrated musical qualities such as shape, dynamics, sense of direction, etc. It’s a subjective call, of course, and even patterns can be exciting for their sheer momentum, odd and changing phrase lengths, and so on.

next section is in wrong place!! fix by moving

Many clapping exercises come across as simple patterns, but they can still be exciting to play and listen to. Here is one of the most well-known rhythmic patterns. It’s titled, “Clapping Music,” composed by Steve Reich, and is for two performers or two groups of players with each group playing in unison. The two groups play the same pattern repeatedly but one group shifts the starting point of their pattern by a single eighth-note every so often. This produces a wonderful kaleidoscope of resultant rhythms, since the phrases of the two groups overlap each other, and where the ‘rests’ (silences) in one group may be filled in unexpectedly by claps from the other. This shifting of patterns against one another is called rhythmic displacement. You can hear a performance and see an animation of the score at

Clapping Music https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzkOFJMI5i8.

The leader first establishes a rhythm cycle, and then claps or vocalizes a relatively short rhythm; everyone mimics the rhythm on the next cycle of rhythm. Of course, the rhythm cannot be too long because what this exercise challenges is the immediacy of the sensory memory, rather than an analytical memory that would be needed for a longer rhythm. But even without giving longer rhythms, there are still important challenges for the development of musicianship in your students.

One important and fun variation is to distribute the rhythm between the two hands on a surface or on different parts of the body. Or the rhythm could be divided between hand clapping and foot stomping. There are long traditions of body percussion in various cultures; hambone is one of the better known. Here’s a URL in case you’re not familiar with it, and there are also many instructional videos for kids. https://youtu.be/m9kaQ3ZKPE0. But you can start by simply dividing the elements of the rhythm between the hands and feet. Getting music students on their feet is really key to a lot of rhythmic perception.

To get you started, you can give your students a rhythmic pattern to clap. A ‘tango’ rhythm is short enough to learn immediately and syncopated without being complicated. Then ask them to stomp it. Finally ask them to mix it up: some stomps and some claps. As the patterns become sufficiently interesting—more musically alive—they become more like ‘rhythms.’ They love it, of course. Here are some ideas presented as notation. (The notation is for the leader, not the participants.)

HOWEVER, the ultimate use of the body to convey a full spectrum of rhythmic devices and all the nuances of rhythmic form and process, articulation, phrasing, etc. is to use the voice. And the most fully developed systems of vocal percussion that I’m aware of are found in Asia. And the most fully developed pedagogy of vocal rhythm is found in India, particularly in the Carnatic tradition in South India. There are many book and videos, so I’m not going to post any instructional material except to illustrate particular points. I will give you just a few links to get you started, but you can get in touch if you’re having difficulty finding an appropriate level of help.

The rhythmic principles & practice of South Indian drumming

Author:Trichy S Sankaran Publisher:Toronto : Lalith Publishers, 1994.

§§§

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HU-Wuc_2AYc

Originally published: July 31, 2008

The Art of Konnakkol

Sankaran

Mrdangam manual : guidebook to South Indian rhythm for western musicians

by Russell Hartenberger

Thesis/dissertation : Thesis/dissertation

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Three Dalcroze Eurhythmics Exercises

The teaching of the Swiss pedagogue, Jacques Dalcroze, is very much worth studying for all teachers and students of music. Dalcroze believed that students who are taught to appreciate music through physicality could develop a deeper sense of rhythm, harmony, and melody. I have experienced a fair bit of Dalcroze studies and, in addition to learning a lot, it also confirmed many aspects of my own approach to teaching. You can find a lot of really good Dalcroze references at http://www.musikinnovations.org/dalcroze.html

There are many creative exercises created by Dalcroze teachers, many of which are based on the following three foundational exercises. These very brief descriptions are not meant to be authoritative; they are included here to give the gist of these three exercise types. They are intended to help students learn more about music through movement and vice-versa.

Follow

There are many possible variations on the idea of a ‘follow.’ The group is given a rhythmic motive to maintain in the legs throughout the exercise, and they are invited to move throughout in the space with the improvised music which is supporting that rhythm. It could be a march, a tango, or even a short, unfamiliar rhythm. While they improvise their movement and maintain the given rhythm in their feet, they are also asked to reflect in their body any and all changes in the music: tempo, register, modality, texture, mood, etc. So they try to follow the music which takes this repeating rhythm through a series of changes in character. It requires the movers to make a distinction between the fixed rhythm and the changing character of the music which is incorporating that rhythm.

Variation: One typical variation employed by experienced Dalcroze teachers is to suddenly stop the music—allowing the participants to sense the rhythm as it is supported only by their own body — in addition to the support of the group, of course.

2. Quick reaction

The leader/musician plays something for the group that will serve as a cue to respond in a particular way. For example, the musician might play a bouncy 12/8 improvisation, directing the group to move in a side-sliding step around clockwise in a circular path, while holding hands with their neighbours on both sides. A quick, trill in the high soprano range might be chosen as the cue for everyone to change the direction of the circular movement, from clockwise to counterclockwise. As they begin to have fun, they naturally move in time to the music, but it is easy to forget to actually listen to the musical content. So while their motor centre is totally engaged and having fun, they still learn to attend to the musical details. The cues can be almost anything you want to have the group listen for. Here’s another example that my university students have really enjoyed.

In this Quick Reaction exercise, they are to listen for the texture of the music. It can be done in many different styles of music. When the music is a single-line melody you move on your own in any direction. When you hear two notes at the same time (either as polyphony (two melodic lines) or a line played with coupled intervals), each person must find a partner and include them in some kind of movement. (They can simply hold hands and move through the space together, or they can stop and make some kind of duo movement in time to the music.) When you hear three or more voices—either polyphonically or a melody played with chords and a bass line—stop moving through the space, form a group of at least 3 people, and invent some kind of movement together. Here’s Greg Ristow, an experienced Dalcroze teacher, leading a Quick Reaction exercise. In this case he invites them to listen for the silence between musical phrases. They learn to anticipate those gaps by learning to listen for the relevant cues in the music. https://youtu.be/zsROX7pQdZM

And here is a short clip from Greg’s workshop when I invited him to York University (Toronto). Here he asks them to change the direction of their movement around the circle when they hear a mordent in the upper register. You can see the development of their listening even within a minute or two.

PUT THE YORK VIDEO HERE

3. Canons (continuous and interrupted)

Dalcroze used two varieties of canon: continuous and interrupted. Canons are essentially call-and-response exercises which typically require the students to remember what they just heard and ‘play’ it back with their movement. The interrupted canon presents the group with a rhythm but the music stops while they take that rhythm with bodily movement. The much trickier continuous canon presents new musical material while they are playing back the last material with their movement. So they must be receptive while also remaining active—a basic demand for all ensemble musicians. It’s a big challenge yielding great satisfaction whether they succeed or not. Here is a video of a young class doing a continuous canon. https://youtu.be/sWRoULMfH9k.

- - - - - - - - - - -

Mirroring

Mirroring can be done in a group setting, but the actually mirroring is usually done between two people. You can also find ways of including more than two people. As with most of the exercises described here, there is no prior musical skill needed. In its basic form, it is essentially an imitation exercise, as with many call-and-response games; As with Dalcroze canons, it can be done with simultaneous or delayed mirroring. It can be limited to upper body movement or it can include the whole body. Obviously, the two people must be able to see each other the whole time, so turning the body away from your partner will not work.

Simultaneous mirroring: One person becomes the ‘leader’ and their partner imitates as closely as possible as the movement continues. The leader’s movement must be slow and simple enough so that their partner can follow along. They can *change roles on their own or on a signal by the teacher/leader.

Delayed mirroring with a beat or with music: The lead person can create a movement to occupy a phrase or a certain number of beats. If the leader’s movement takes 6 beats, then the follower’s movement must also fill 6 beats. (The teacher/musician can suggest working with a longer or shorter duration.